“I would like to tell you how genuinely proud I am to have men such as your son in my command, and how gratified I am to know that young Americans with such courage and resourcefulness are fighting our country’s battle against the aggressor nations.”

—Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, Allied air chief in the southwest Pacific, in a 1943 letter to my grandmother, Clara Grady, noting her son’s receipt of the Distinguished Flying Cross

Kind of a gloomy November morning here in The Duck! City.

But not as gloomy as it must have been back in the Forties, when the men of the 433rd Troop Carrier Group were fighting the Japanese in and around New Guinea.

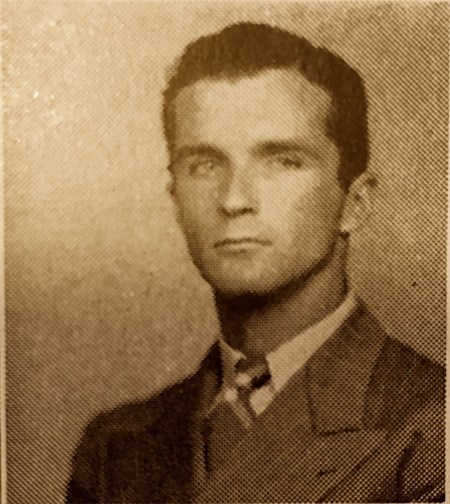

I was surfing lazily across the Innertubes when I stumbled across a Library of Congress collection of interviews with some of the men who served in the 433rd with then-1st Lt. Harold Joseph O’Grady, who was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1943 but rarely discussed his wartime service, even with family.

One of the interviewees, another Harold — Harold E. “Vick” Vickers — discussed his service from right here in Albuquerque back in 2005, and again in 2012. What a small world it is.

Vick wanted to be a pilot like my old man, but didn’t have the vision for it — “You had to have perfect eyes,” he said — and so he served in a support role, in operations, with the 433rd.

And he had to take ahold to get that job. He enlisted in what then was called the U.S. Army Air Corps (later the Army Air Forces), but instead found himself in the Signal Corps. Vick wasn’t having any of that — he fought to be Air Corps and got his wish.

“Be careful what you wish for,” they say. And they ain’t just a-woofin’.

Vick was supposed to ship out — for real, on an actual ship out of San Francisco — but wound up ordered to travel to New Guinea with the air crews in a formation of brand-new C-47s.

His plane blew an engine and missed the departure, and once the aircraft was squared away his crew had to play catchup, solo, with a brand-new navigator, island-hopping across the Pacific to Brisbane and finally to Port Moresby, New Guinea, which had yet to be pacified by the Allies.

And that’s where things got really hairy. Not a memoir for the faint of heart. It gave me some idea of why the old man might not have been eager to share his war stories with snot-nosed kids.

Here’s to Vic, Hank, and all the rest of the men and women who did their best in far-off lands, especially the ones who never came back to tell their tales.